Candy Rising... and the triple-decker novel

Q : What does Lambeth Books' launch novel

Candy Rising... have in common with Tolkien's

The Lord of the Rings,

Austen's first four novels, and even Mary Shelley's

Frankenstein?

A: The power of 3.

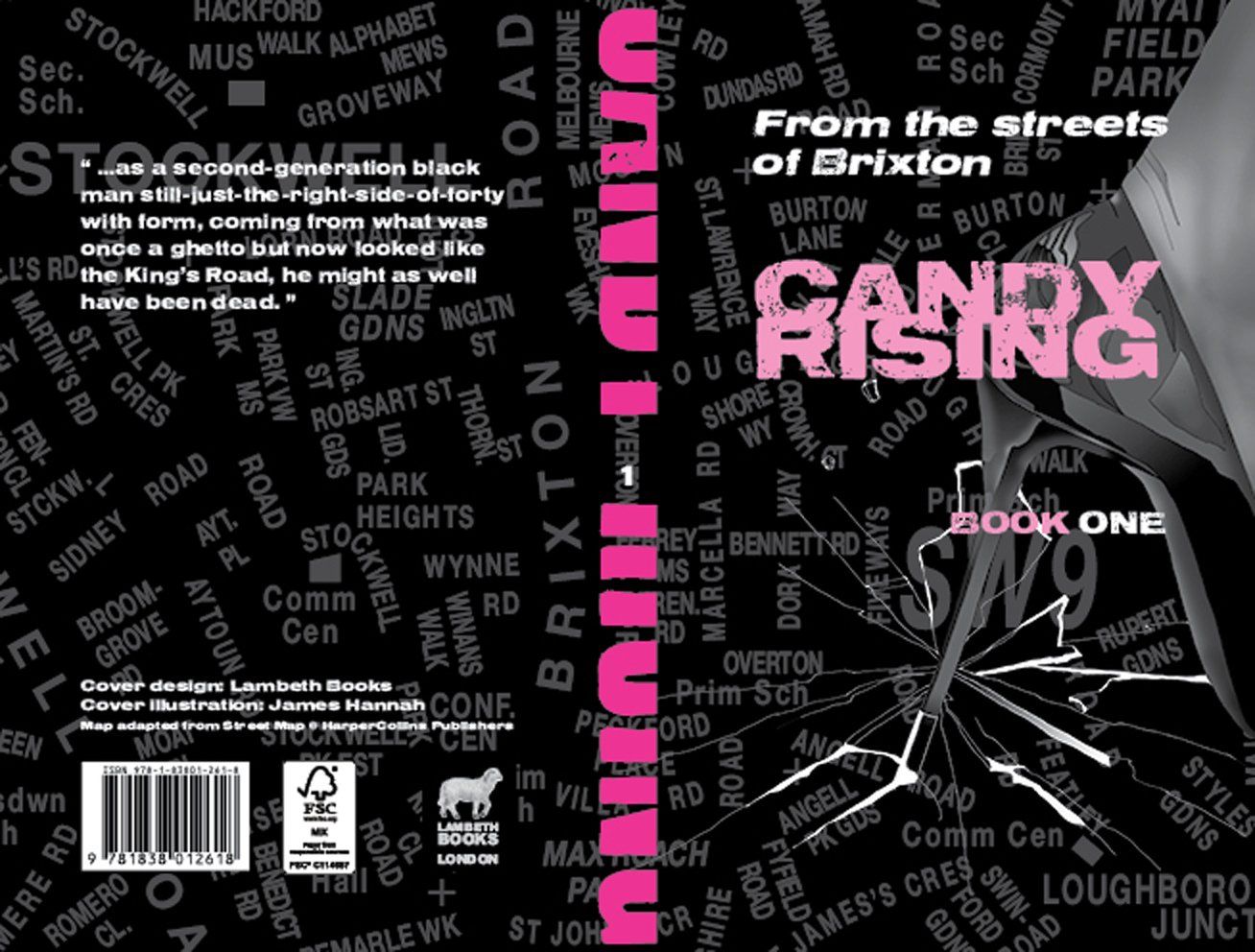

Lambeth Books is extremely proud to be issuing its launch novel Candy Rising in three 'books', with the first being published in June 2020, the second a year-on in June 2021 and the third book appearing in the autumn of 2021.

'Triple-deckers' (as they were popularly referred to in their heyday), novels published in three 'volumes', are not that unusual, in fact they have a vibrant history, mostly garnered by their close relationship to the subscription and lending libraries of the nineteenth century, simply because they were the publishing format that was the most profitable for the suppliers (the publishers and further on the distributors) and the most affordable for their audience (the flourishing middle-class).

Q: So what actually is a 'triple decker'?

A: A novel broken down into three volumes for either financial reasons and or restraints and or to bolster the impact of the novel.

But let us make this very clear right now: a triple-decker, also known as a three-volume novel, is not a trilogy, although they are sometimes confusingly referred to as that. A trilogy is a collection of three related but separate or even disparate novels. They are novels that have been written or bought together conceptually, because they relate in some kind of way, to make up a set of three, either in the flow of narrative or in the subject matter or quite possibly by some other similarity or power of association. In this way the concept of a trilogy can be given retrospectively after the first, second or third book has been written or even published. Furthermore the accolade might not be the brainchild of the author at all but that of their publisher who wants to hold onto the tails/tales of his or her author by exploiting the author's reputation and the interest in each of the books, in order to build up a 'common sense' of continuity and cohesion in the three of them so as to sell more of them, and more than likely, in a new edition. Chinua Achebe's 'The African Trilogy' is a good example here [1] and further considering these three works of Achebe's, the next question to ask would be:

Q:

did Mr Heinemann or Mr Achebe come up with the idea of these three novels coming together as a trilogy? Likewise, we could ask the same of sci-fiction's 'distinctive new voice' [2] Tade Thompson, whose 2016 novel

Rosewater, first published by the US publisher Apex Publications and was later issued by Orbit at 'The Wormwood Trilogy' [3] and it might just be that the use of the term 'trilogy' in this instance has been adopted in Thompsons' case to speak specifically to the fans and consumers of a particular genre of novels, that of sci-fiction writing, who are far more familiar with the concept of a trilogy,

The nineteenth century saw the very rapid development of the format of the novel in the the UK, that which would eventually evolve into what we now call 'fiction'. Printed editions were extremely expensive to produce in the early decades and the sale price obviously had to reflect the costs of production, hence the rise (and the subsequent and inevitable fall) of the subscription and lending libraries (Mudies and WH Smith being the obviously examples here), who took on the huge cost of purchasing the novels and then loaned the copies out to their members or subscribers. It is said that two thirds of novels published in book form in the nineteenth century were in three-volume sets. Mrs Shelley, Miss Austen, the three Miss Brontes, even Miss Evans did so through their publishers. Likewise Mr Scott, (whose novel

Kenilworth was apparently the first novel ever to be published in three volumes), all the way through to Messrs Dickens and Collins. And it was only with the mechanisation in the printing industry which dramatically cut the cost of production that the three-volume novel came to an end for, when the libraries stopped ordering copies, they ceased to exist.

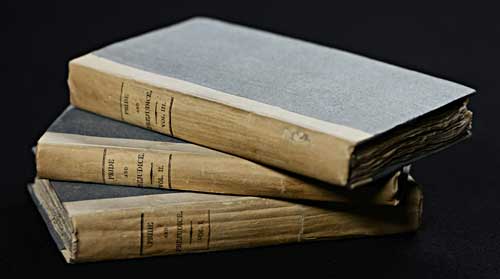

Just imagine being back in in the early-mid 1810s when Austen's first four novels [4] reached the day-rooms of middle-England and rattled the tea sets with her awfully dry wit and nullifying acerbic observations of the social morals and mores of the most avid of afternoon tea drinkers, the upper middle class, those who were her immediate superiors, not her contemporaries. How much it would have cost to have purchased the six books and to have had them delivered to you by stage coach, to have received them, possibly with the leaves still uncut and the naked pale blue boards pristine. Or, shifting a few years forward to 1818, when Mary Shelley's

Frankenstein was issued in three volumes [5], you had received your copy, on the coldest day of the year so far that January, in a heavy flat parcel that, when you opened it, revealed folds of uncut sheets, packaged so so that you could take them to your favourite binders in your nearest town, or possibly even to London. This certainly suggests 'volumes' rather than 'books', and a passion and income far larger than the average book readers today. And yet against the odds and in total opposition to most unknown writers today, who self-publish and rely on the internet to sell their novels, it was the success of these costly limited edition triple-deckers volumes of writers that gave impetus to the demand for 'novels'.

But now we come to where the nineteenth-century and contemporary understandings of what a 'volume' is break away from one another. For back then they offered the latest in contemporary fiction. Whereas to think of a 'volume' nowadays suggests antiquity, libraries, heavy reference books, back catalogues, directories, reports and, at their most heavy weight and specialised, legal tomes, with the latter being fundamentally technical, if not ideological, all a far cry from the page turners they once encapsulated [6]. Yet still, the three-volume format has managed to survive beyond the nineteenth century, although in an evolved form, for example we have Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings 'trilogy' [7] right in the middle of the twentieth century and even in the twenty-first we see Haruki Murakami's 1Q84 [8], although, but this the important distinguishing factor, they are 'books' or as in Tolkien's 'trilogy' pairs of books.

Confused? If you weren't it would be a surprise. Maybe Lambeth Books' launch novel Candy Rising can help in understanding these, at times, very subtle, if not sometimes overlapping, sometimes misappropriated differentiations between the three formats, and what factors come to play to impact on the finished product. Originally the intention of Lambeth Books with Candy Rising was to issue the novel in its entirety but there were concerns that the density (forced by the tight layout required for the size of book chosen to meet financial constraints) and the corresponding 'digestability' of such a book might put off some from reading it, although, when it comes to the defining characteristics of the genre, such dense paper-saving editions is the standard format of hard boiled fiction (see the previous blog, 'Hard boiled Candy' for more on this). So these factors, combined with production restraints, forced Lambeth Books to issue the novel in three 'books' not 'volumes', for each book follows the natural breaks in the narrative, breaks which could be seen as specific 'time chambers'. Splitting the novel into three also seemed the better option for, although the pace of the story would be disrupted by its staggering, it enabled the imprint to not just to maximise its potential for sales and awareness of the new author (who although wishes to remain anonymous is still an author) but also to celebrate and exploit the opportunity to offer three, limited edition, numbered books. So the format of issue became a unique part of design and presentation of the novel, as much as it was a reflection of the novel's inherent structure, as much as it was about meeting deadlines and financial constraints. However, unlike most other triple-deckers, Lambeth Books' debut novel offers the novel in three unequal books and in this way breaks with the tradition of the three volume novel, for an economy of balance presided over these earlier editions and many of the authors in the nineteenth century were asked to write to certain specifications (the pagination of 900 pages being a fundamental part of what was specified).

so:

Q: Is Candy Rising a trilogy then I hear you ask?

A: No. It is a story, or rather, a novel split into three parts, books, just like the triple-decker volumes of the nineteenth century used to be.

And so it goes on.

There certainly was and still is something in the power of three.

Yours,

The publisher,

Lambeth Books.

Post script: Just as I came to the end of writing this blog I stumbled across a site dedicated to 'Britain, Representation and Nineteenth Century History' (the BRANCH collective) which has a very 'scholarly' article about the demise of the triple deckers in the UK towards the end of the nineteenth century, it also alludes to Kipling's poem 'The Three-Decker', check it out at https://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=richard-menke-the-end-of-the-three-volume-novel-system-27-june-1894

<<Watch out for further blogs on

anonymous writing and

the costs of production, a comparative study of 2020 to 1891.>>

Footnotes:

1 Things Fall Apart, Achebe's debut novel was first published in 1958 by William Heinemann. It was followed by No Longer At Ease in 1960 and Arrow of God in 1964. At some point it became known as

'The African Trilogy'.

2 See the inside upper cover of Rosewater, book '1' of 'The Wormwood Trilogy' by Tade Thompson, Orbit, first UK edition, 2018.

3 Orbit, an imprint of Little Brown Book Group, issued the first UK edition of Rosewater, as the first book, '1' in 'The Wormwood Trilogy'. The second book, '2', in the 'trilogy', The Rosewater Insurrection was

published by Orbit in 2019 and the third book, '3' in the 'trilogy', The Rosewater Redemption was published by Orbit in 2020.

4 Sense and Sensibility was published in 1811, Pride and Prejudice was published in 1813, Mansfield Park in 1814 by Thomas Egerton of Whitehall, London, and Emma in 1815, by John Murray, London.

5 It really is hard to imagine that only a few years, and, if we take the Shelley's move to Marlow in Buckinghamshire in March 1817 as a fixed date, only 42.9 miles, separated these two female literary

medusas at that moment in time.

6 And further juxtaposed to this are the most contemporary formats of books, be they the best-selling 'novels' or 'trilogies', that have become so inconsequentially light in the way of audio books and e-

books that they fail to have any volume, or mass, what-so-ever.

7 The Fellowship of the Ring (Books I and II) was first published in the UK on 29 July 1954, The Two Towers (Books III and IV) followed on 11 November 1954 and The Return of the King (Books V and VI

plus six appendices) on 20 October 1954.

8 IQ84 was published in Japan in three hardcover volumes by Shinchosha Publishing Company, Ltd., 'Book 1' and 'Book 2' were both published on May 29, 2009 and 'Book 3' was published on April 16,

2010, although it wasn't Murakami's first 'three-volumed' novel, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle saw the original Japanese edition released in three parts, which make up the three 'books' [Book One of the

Thieving Magpie, Book Two of the Prophesying Bird, Book Three of the Bird-Catcher Man] of the single volume English language version.